The idea for this article began with a question that I pondered yesterday during the broadcast of the Brooklyn Cylcones, the Mets’ High-A affiliate, and the Hudson Valley Renegades: Do relief pitchers tend to work at a faster pace than starting pitchers? While that is not the scope of this particular piece, it got me thinking about the clock and its impact on Major League Baseball in year two.

The idea for this article began with a question that I pondered yesterday during the broadcast of the Brooklyn Cylcones, the Mets’ High-A affiliate, and the Hudson Valley Renegades: Do relief pitchers tend to work at a faster pace than starting pitchers? While that is not the scope of this particular piece, it got me thinking about the clock and its impact on Major League Baseball in year two.

In poking around on Baseball Savant’s pitch tempo data (the average time it takes for a pitcher to come home), there were a few interesting things that stood out. Before we dive in, a note – Baseball Savant’s pitch tempo metric does not measure the time on the pitch clock, but rather the time between the time the pitcher releasing a pitch and him releasing the next pitch (includes getting it back from the catcher, etc.). They measure that on average six seconds elapses from “start of delivery” to “receiving return throw” from the catcher.

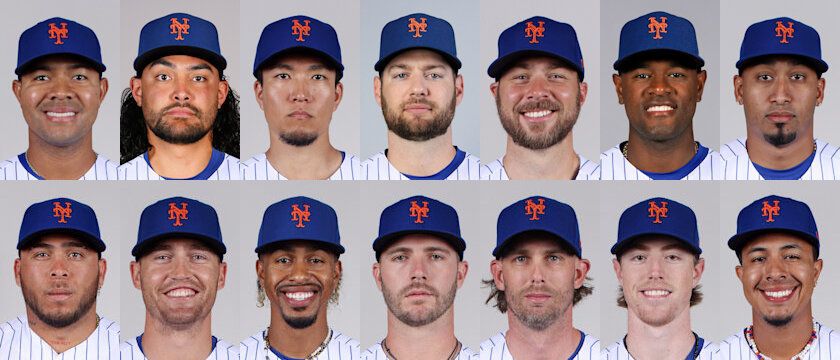

The three quickest-working pitchers on the team this year (min. 50 pitches) are Luis Severino, Adrian Houser and Sean Manaea – all players brought into the organization this offseason. That is more of a coincidence than anything else I suspect, as there are some others who were added this year who are on the other end of the spectrum.

Severino is a really interesting case. In his best years with the Yankees, he was always a pretty fast worker. In 2017 and 2018 his average tempo was 14.8 seconds between pitches with the bases empty, and 21.9 and 21.3 seconds with runners on, respectively. Those numbers climbed some in his injury-plagued 2019-2022 seasons, but last year he reverted some to form – 13.9 with bases empty, and 18.8 with runners on.

In 2024, Severino has worked quicker than ever before: a 13.0 rate with no runners on, and 17.2 with runners on. His Fast % is a career-high 75.4%, which is top 50 among all qualified pitchers. His tempo with the bases empty is 23rd in MLB. This is a marked shift in his pitching tempo and it seems to be working well as he is enjoying a bounce-back season as Brian Joura wrote about a few days ago.

Another veteran arm with a large body of work before the pitch clock era, Jose Quintana, has seen a similar reversion to his early-career tendencies. Quintana was always one of the quicker workers with the bases empty in his career, averaging between 15.3 seconds and 18.5 seconds between pitches until 2019-21, when he was above 19.0 seconds each year. However, he was always the kind of pitcher who significantly slowed down with runners on base, taking between 23.0 and 25.2 seconds in most seasons.

In 2023, Quintana sped up to 15.6 with bases empty and 20.1 with runners on, a drop of 2.0 and 2.9 seconds in each situation, respectively. This year he has undergone a slight shift, taking slightly longer with the bases empty (16.3) and working slightly quicker with runners on base (19.4). Quintana’s results have been worse this year in both situationals, so it’s likely this is a move done more of a comfort standpoint, and less of a results-based shift.

The slowest workers on the staff with the bases empty, Adam Ottavino (18.2), Sean Reid-Foley (18.5) and Tylor Megill (18.9), are all among the 20 slowest pitchers in MLB who have thrown at least 50 pitches this year. Megill checks in as the fourth-slowest with only San Diego’s Yuki Matsui, the White Sox’s Mike Clevinger and Cleveland’s Xzavion Curry taking longer among pitchers with that qualifier. For good measure, Reid-Foley is the ninth-slowest pitcher while Ottavino is 20th (but with runners on, Ottavino is ninth-slowest).

The upshot of all of this is that the Mets, like many other staffs, have a mix of quick and slow workers, there is nothing groundbreaking about that. While we are way down the road into year two of the pitch clock era, it is interesting to see how that is affecting some of the veterans who came up before the clock, and how different players have adjusted from year one to year two.

To me, the pitch clock has essentially solved the problem of pitchers wasting too much time. With the clock in place, I’m okay with whatever tempo they wish to use.

The pitch clock has been a success. I think they still need to tinker with the SB rules. I’m fine with more runners taking off. But it’s just too easy, like if they started approving 300 feet fences down the line.

My solution – which I doubt many will endorse – is to do away with all balk rules.

I was not in favor of the pitch clock until I realized how much time it chops off of a game. It reminds me more of a high school game now where the pitcher gets the ball throws a pitch gets the ball back throws a pitch, etc. What still drives me crazy is the limit of pick off throws or a step off the mound before the potential of committing a balk. Also believe that the quicker pitching tempo will hinder older pictures, who could use a little bit of extra time in between throws. Another benefit of the pitch clock is the stops batters from stepping out every third pitch to fasten their batting gloves or to try to psych out the pitcher.