February 13, 1920 is one of the most important days in the history of baseball. It was on that day that Andrew “Rube” Foster met at the YMCA on 18th and Vine St. in Kansas City, Missouri with owners of six other black baseball teams and formed the first Negro National League. At its peak, professional baseball was the third-largest black-owned business in the country.

Foster first emerged as a star pitcher at the turn of the 20th century, and he quickly became one of the most colorful and well-known black ballplayers. He got his nickname after beating the enigmatic Philadelphia Athletics ace Rube Waddell in an exhibition game, while others called him the “Black Christy Mathewson.” By 1920 his pitching career was winding down and he was more consumed with managing his powerful Chicago American Giants club. Foster knew that for black baseball to survive, it needed an organized league.

The NNL fielded teams throughout the Midwest in Chicago, Cincinnati, Dayton, Detroit, Indianapolis, Kansas City and St. Louis. Through the years, other major black leagues such as the Southern Negro League, the Eastern Colored League, a separate NNL iteration and the Negro American League would all pop up.

The Negro Leagues were nothing like pop culture would later portray. Here’s the legendary Buck O’Neil to ESPN:

“In the Negro Leagues, we rode in the best buses money could buy. We stayed in the best hotels — they just happened to be black-owned. We ate in the best restaurants — they just happened to be black-owned. First class.

We played in Yankee Stadium, and we’d fill up Yankee Stadium. That night, we’d come down to Harlem. We’d go into the different places. During that era, all of the nightspots had live music. We’d hear these guys: Duke Ellington playing in New York City after the ballgames. Then we’d go from there to Philadelphia, the Earl Theatre in Philadelphia, and it could be Count Basie playing there. We’d go down to Washington and the Howard Theatre, and we might see Redd Foxx and Moms Mabley. It wasn’t like ‘The Soul Of The Game [a 1996 TV movie about the Negro Leagues].’ THAT wasn’t Negro League baseball. No. First class.”

After baseball finally began the process of integrating, the leagues began to die out. The second NNL collapsed in 1948, but the NAL held on until around 1960. Some teams, like the Indianapolis Clowns held on until much later as barnstorming teams.

Though the Negro Leagues are long gone, the legacy of those who played there still lives on. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City is routinely voted as one of the best museums in the United States, and there is always new research coming out about long forgotten teams and players.

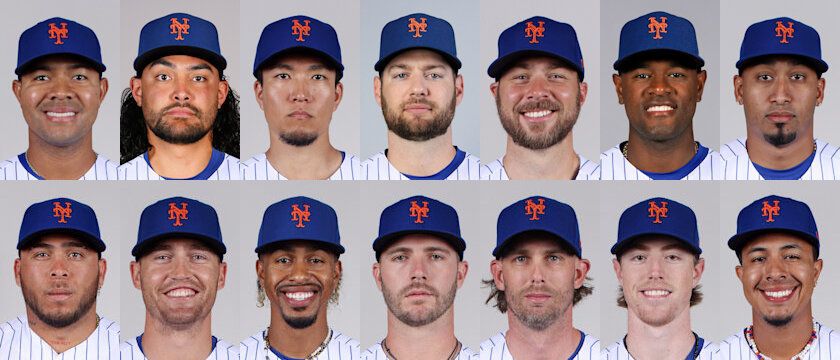

Even though the New York Mets did not come into existence until 1962, after the death of the NNL and NAL, they still claim four players in their history who played in the Negro Leagues.

Charlie Neal is forever linked to Mets history by being in their first-ever Opening Day lineup. Batting third and playing second base, Neal went 3-for-4 with a home run and two RBIs in the Mets loss to the Cardinals on April 11, 1962. He had an eight-year MLB career with the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers, Mets and Cincinnati Reds and made two all-star appearances.

Neal as only 16 years old in 1947 when he began playing for black semipro teams in the south. He even suited up for the Atlanta Black Crackers of the Negro Southern League. There is currently no record of Neal’s statistics. In 1949 he was driving a truck for a meat-packing company when he was signed by the Dodgers. He advanced through their minor league system until finally sticking in the majors in 1957.

George Altman was a hard-hitting outfielder for the Chicago Cubs in the late 50s and early 60s. He led the National League in triples (12) in 1961 while swatting 27 home runs and posting a .303/.353/.560 slash line in his first of two consecutive all-star seasons. In 1964, Altman played 124 games for the Mets, batting .230/.363/.332 with only nine homers and one triple at age 31. In total he played nine seasons in the majors including two stints with the Cubs, and one year each with the St. Louis Cardinals (1963) and Mets. He spent the final eight seasons of his career playing in Japan, where he became one of the most feared sluggers in the Japan Pacific League.

Before he broke in with the Cubs, Altman began his professional career after graduating Tennessee A&I (now Tennessee State) in 1955 as a member of the famed Kansas City Monarchs. He only lasted three months as the Monarch’s legendary manager Buck O’Neil recommended Altman to the Cubs, who signed him for a sum of $11,000. Much like Neal, we have no known record of Altman’s statistics with the Monarchs.

The Mets trade for first baseman Donn Clendenon is an integral part of the 1969 Miracle Mets narrative. He provided the offensive spark the team needed to compliment Tommie Agee, and went on to win World Series MVP. But his story outside of his 12-year MLB career is fascinating. Clendenon’s father died of leukemia when he was only six months old. When he was six, his mother married former Negro League player Nish Williams.

Williams coached Clendenon in his youth and even while he was in college. He brought his friends Jackie Robinson, Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe to give Clendenon pointers. Clendenon was ready to accept a scholarship to UCLA, but a coach from Morehouse College in Atlanta convinced his mother he should stay close to home. He played football, basketball and baseball at Morehouse, and had professional offers from the Cleveland Browns and Harlem Globetrotters upon graduation. Of course, Williams steered Clendenon to sign with the Pittsburgh Pirates. As a freshman at Morehouse, Clendenon was assigned an upperclass “Big Brother” as a mentor. The future big leaguer was assigned none other than Martin Luther King, Jr.

Unlike Neal and Altman, Clendenon never played in the professional Negro Leagues, but did suit up for the Atlanta Black Crackers, then operating as a semi-pro outfit, during his summers. The Black Crackers were managed at that point by Williams who helped mold him into the kind of player that MLB teams would sign. His time with the team undoubtedly helped him become the player who would help the Mets take down the mighty Baltimore Orioles in the World Series.

Willie Mays is the greatest baseball player since the sport was integrated in 1947. Frankly the only player who has a chance to challenge him for that crown is Mike Trout, but that’s a debate for another day. As Mets fans we know that the Say Hey Kid had his swan song in Major League Baseball with the Mets from 1972-73, but many don’t know that he began his professional career at age 17 with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League.

Different databases differ on Mays’ exact statistics in 1948, but we know he hit at least one home run and it’s reasonable to assume he batted somewhere in the mid-.200s. With MLB’s recent decision to elevate the Negro Leagues from 1920-1948 to major league status, those hits and that home run will soon be added to Mays’ official career totals, giving him 661 career home runs.

In 1949 and 1950, Mays continued to play for the Black Barons, and through his work with manager Piper Davis, learned to hit a curveball and posted batting averages north of .300 in both seasons before he was signed by the New York Giants. He is one of 10 former Negro Leagues players who have been elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame after playing in MLB.

Joe Vasile is a broadcaster for the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders (NYY, AAA) and Bucknell University. He hosts the baseball history podcast, Secondary Lead.

Sources:

· Negro Leagues Baseball Museum eMuseum. “Willie Mays”. https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/mays.html.

· Spencer, Sheldon. “Buck O’Neil”. http://www.espn.com/espn/page2/story?page=questions/buckoneil. ESPN Page 2.

· Baseball-Reference

· Seamheads Negro Leagues Database

· SABR Bio Projects:

Terrific piece, Joe!

For anyone who’s never been, there’s a terrific site that covers the Negro Leagues called Seamheads run by Mike Lynch, who’s a great guy. Joe made reference that different sites have different numbers for Mays. Seamheads has him at .239/.349/.310 as a 17 year old on the Birmingham Black Barons in 1948. Nobody else on the team was younger than 23.

http://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=mays-01wil

Thanks! Honestly Clendenon’s story is what surprised me the most in all of this. I had no idea.

Outstanding article, Joe! I learned a lot reading this, most especially about the real truth of the Negro Leagues, as communicated by Buck O’Neill. Fascinating. Thank you for writing this!