There are many ways to enjoy watching a baseball game and one of those is to appreciate seeing something that you rarely see, or perhaps have never seen before. Friday night, the summer collegiate baseball team that I work for had a couple of things that made me smile. One was a four-pitch inning, which you might see a couple of times a year. The other was a triple play, something which was new to me at this level, despite 15 years with the organization.

There are many ways to enjoy watching a baseball game and one of those is to appreciate seeing something that you rarely see, or perhaps have never seen before. Friday night, the summer collegiate baseball team that I work for had a couple of things that made me smile. One was a four-pitch inning, which you might see a couple of times a year. The other was a triple play, something which was new to me at this level, despite 15 years with the organization.

While those things were happening in a Coastal Plain League game on Friday, the Mets had their own unique thing going on. Tylor Megill gave the Mets six strong innings and the Mets won, raising their record to 19-1 when their SP goes at least six innings. While it’s not something that immediately jumps out to you like a triple play, it’s incredibly difficult for a team that plays at a sub-.500 clip to go 19-1 in, well, anything.

One of the classic ways to view probability is to look at the results for flipping a coin. The beauty of the coin flip is that there are only two outcomes – heads or tails – and each is equally likely to happen. So, let’s say you’re going to flip a coin 20 times. What’s the probability that you will get 19 heads and one tail?

If you flip a coin once, you’ll get H or T – or two potential outcomes

If you flip a coin twice, you’ll get HH, HT, TH or TT – or four potential outcomes

If you flip a coin three times, you’ll get HHH, HHT, HTH, HTT, THH, THT, TTH or TTT – or eight potential outcomes

If you flip a coin four times, you’ll get HHHH, HHHT, HHTH, HHTT, HTHH, HTHT, HTTH, HTTT, THHH, THHT, THTH, THTT, TTHH, TTHT, TTTH or TTTT – or 16 potential outcomes.

Each time you flip, you’re adding twice as many potential outcomes. Mathematically, this is an exponent. The first case above would be 2 to the first power, the second case, 2 to the second power, the third case, 2 to the third power and so on.

If we flip our coin 20 times, there will be 1,048,576 potential outcomes. That’s 2 to the 20th power. We were curious how often we could get 19 heads when we flipped a coin 20 times. There are 20 different ways this can happen and it’s easy if we just look at the way we can wind up with one tail. We can get it the first time we flip the coin. Or the second. Or the third. And on and on until we reach 20.

So, there are 20 ways we can flip 19 heads in 20 times. That’s out of 1,048,576 potential outcomes. If we divide 20 by 1,048,576 we get .000019073 – which is not a great chance. To put it in percent terms, there’s a .0019073% chance of flipping 19 heads in 20 tries or roughly two one-thousandths of a percent chance of that happening.

We did this math homework to get a ballpark estimate of how likely it would be for a team to go 19-1 when its starting pitchers went at least six innings. Like flipping a coin – there are only two outcomes here. Either you win or you lose. But, unlike a coin, there’s not a 50-50 chance of getting either outcome. A few days ago, MLB teams had a 495-265 record when a starter went at least six innings. So, instead of a 50% chance of winning this type of start, there’s a 65% chance of winning.

My friend Matt Bruce helped me with the next part. According to Matt, to find the probability of going 19-1 in 20 trials when you have a 65% chance of getting a favorable outcome, you have to use the following equation:

20 * 35% * (65% to the power of 20)

Fortunately, we have online calculators to help find the answer to what the result of a percentage with an exponent is, as it’s not something you’d want to do by hand. And CalculatorSoup’s Exponents Calculator spits out .000181245 as our answer. When we multiply that by .35 and by 20, we get .0012687 as our answer.

So, from a purely mathematical look, there’s about 1/8 of 1% chance at going 19-1 in 20 games where your starting pitcher goes at least six innings. That’s exceptionally rare and hopefully something you can appreciate.

Of course, there’s more at play than just overall odds and probabilities. It’s a lot easier to post a good record in these situations if your offense scores six runs a game than if it scores four runs a game. And it’s easier if your SP turns in his outings of at least six innings against the dregs of the league, rather than the elite squads. No doubt there are other variables to potentially consider here, too.

The hope is that by getting that 65% chance of recording a win by looking at the results of all 30 MLB teams, we’ve addressed those variables, known or otherwise, at least to some extent. Still, if somehow we knew all of the correct variables to use, the number for the 2023 Mets would be different than 1/8 of 1%. But it’s not going to be different to a very large degree. It’s not going to go to a 5% chance, or anything like that. If anything, given what we know about the overall quality of this year’s Mets, the odds of going 19-1 would likely become greater, rather than the other way around.

And just like with flipping a coin, just because you went 19-1 in one 20-trial batch, that doesn’t mean you’ll go 19-1 in the next 20. And on Saturday, we saw Kodai Senga go 6.2 IP in a game the Mets lost.

Yet even though a team’s record in 20 games where their SP goes at least six innings does not have any in-season predictive value, it does seem like perhaps we can look at this information on a macro level and make some observations.

Last week when these numbers were ran, MLB teams won games where their SP went at least 6 IP at a 65% clip. At the same time, when their starter gave fewer than 6 IP, teams won 40% of the time. The numbers don’t add up to 100 because there are games when both teams had outings in the same category at the same time, either both gave starts of at least six innings or starts where both gave fewer innings than that.

Knowing this information, you might assemble a pitching staff with veterans with a track record of going six innings or more in a start. Last year, Max Scherzer (19/23) and Justin Verlander (22/28) went at least six innings in a little over 80% of their starts. Jose Quintana wasn’t quite at that rate but was pitching better and going deeper as the season progressed.

Last year, the Mets went 62-21 when their starter gave at least six innings, a .747 winning percentage. If you could assemble a staff that gave more starts of this type, chances are your overall record would remain strong, even if not to last year’s 101-win pace.

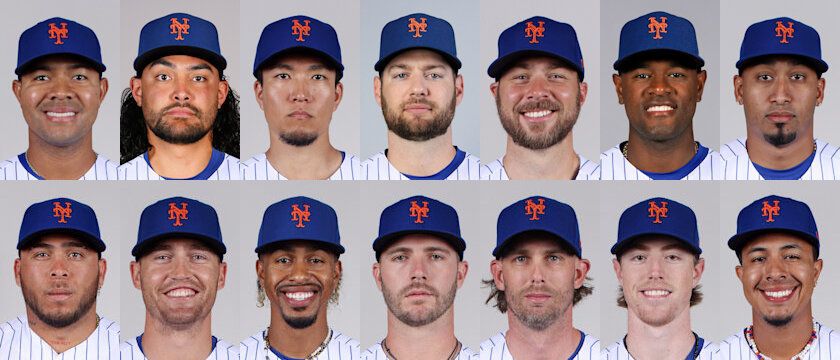

Now at 19-2, the Mets have an extremely impressive .905 winning percentage when their starter goes six innings or more. But last year, they got these long outings 51% of the time. This year, it’s 21 times in 70 games, or 30% of the time.

Hopefully, on a percentage level, the team produces twice as many starts of at least six innings over the final 92 games. And even though odds are stacked against them producing a .905 winning percentage in those games, they’ll no doubt be a massive improvement over the .286 winning percentage the Mets have currently when their SP fails to complete six innings.

What really looks bad is if you subtract the 19-2 record. You have a 13-35 record.

I do appreciate thongs you don’t see. I had never seen a steal of home in a game until Kiner-Falefa did it. It was just a shame it was against our team.

Yep, it’s actually 14-35 which is the .286 winning percentage mentioned in the last graph.

I’ve seen several steals of home as part of a double steal. I’ve seen one steal of home straight up in person, when I saw Billy Hatcher steal home at Fenway Park.

Running the probabilities for 19-2 and 65% win probability is still just 0.7%, top 1 percentile still.

I guess the only way to frame it is when the things go right, everything goes right and when things go bad, everything goes wrong

The starting pitcher gives up too many runs in the first inning. Scherzer, Verlander, Carrasco, Megill, Senga and Peterson have significantly worst WHIP this year than last.year. They are throwing more pitches and worse pitches per inning. It results in shorter outings. They can’t upgrade five starters pitchers in the trade. They can upgrade the middle relievers and have a better bridge to the 8th inning.