The idea of the farm system is to develop the talents of future MLB stars, like the five players listed above, along with role players and even guys who come up for a cup of coffee. But those three groups are far from equal. In the moment, we love the story about the guy who bounced around in the minors for 10 years and finally gets his chance in the majors. It’s the ultimate underdog story and you’d be a cruel bastard if that didn’t warm your heart. But that’s not why MLB teams have farm systems.

In an ideal world, hitters wait for a pitch they can drive and when they get it, they turn on it and deliver an extra-base hit. The ancillary benefit of waiting for a pitch to drive is that a hitter will generate walks this way, too. Walks are good. They’re not as good as an XBH but they’re still good. And the minor league system is the same way. You have a farm system to generate stars. The ancillary benefit is generating role players. Those role players are good. They’re not as good as stars but they’re still good.

Let’s look at the players the minor league system has generated in the Mets360 era, which starts in 2010. The extra-base hit/star is Alonso. The walk/role player is Kirk Nieuwenhuis. The reached on a catcher’s interference/underdog story is T.J. Rivera.

The simple fact is that you cannot have a minor league system without the vast majority of the players being guys whose absolute ceiling is underdog story and whose most likely outcome is being released after four or five years.

And that simple fact is why you can’t take the “average age” of a player at a given level seriously. Who cares if the average age of a hitter at Binghamton is 24.3 years old when the overwhelming majority of those hitters have an underdog ceiling?

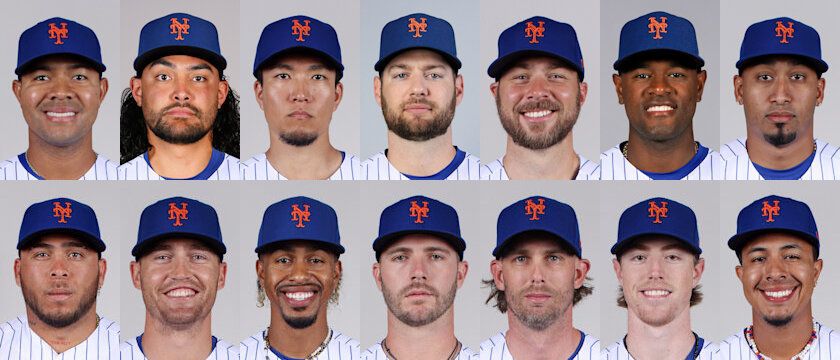

Instead, let’s look at the best hitting prospects, ones who’ve amassed at least 2,000 PA in the majors, that the Mets’ farm system has developed since 2010 and see what age they were at various full-season levels prior to making their MLB debut:

| Name | AAA | AA | Hi-A | Lo-A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jeff McNeil | 25/26 | 24/26 | 22/23/25 | 22 |

| Brandon Nimmo | 22/23 | 21/22 | 21/22 | 20 |

| Michael Conforto | 22 | 22 | ||

| Lucas Duda | 24 | 23/24 | 22 | |

| Pete Alonso | 23 | 22/23 | 22 | |

| Ike Davis | 23 | 22 | 22 | |

| Ruben Tejada | 20/21 | 19 | 18 | |

| Travis d’Arnaud | 23/24 | 22/24 | 21 | 19/20 |

| Wilmer Flores | 21 | 20 | 18/19/20 | 16/17/18 |

| Juan Lagares | 24 | 22/23 | 21/22 | 19/20/21 |

| Amed Rosario | 21 | 19/20 | 19/20 | 18 |

We’ll take a look at each of these players in more detail but first let’s come up with an average. It’s tough to come up with an average because of people playing multiple years at various levels. So, we’ll break that down three different ways. The first is to count each partial year at a level as a full year. Our 11 players had 14 “years” at Triple-A, with four guys spending parts of two years there while Conforto did not play there before making his MLB debut.

AAA – 22.9

AA – 22.1

Hi-A – 21

Lo-A – 19.1

Next, let’s calculate our average age by level giving a player only one age at each level. Here, we’ll do the oldest age he was at a level. So, McNeil’s Lo-A age is 22, Hi-A age is 25, AA is 26 and AAA is 26.

AAA – 23

AA – 22.3

Hi-A – 21.5

Lo-A – 19.8

Finally, let’s calculate our average age by level, giving each player only his lowest age. So, McNeil would be 22 at Lo-A, 22 at Hi-A, 24 at AA and 25 at AAA.

AAA – 22.6

AA – 21.5

Hi-A – 20.7

Lo-A – 19

Pretty much any way you look at it, the average age should be 23 for AAA, 22 for AA, 21 for Hi-A and 19/20 for Lo-A. Before we get to our 11 hitters in the chart above, let’s look at underdog story Rivera. His ascension to the majors was delayed not because of injury but rather because that’s how long it took him to prove worthy of a shot. Since making his full-season debut in 2012, here were his games played by year: 128, 125, 115, 110 and 105 before getting his first taste of MLB. Some guys like Rivera spend a lot of time in the minors because they weren’t stars. Other guys spent a lot of time in the majors because of injury.

McNeil – He was listed first because this is the case everyone points to when thinking that a prospect’s age by level is higher than it should be. McNeil didn’t make his MLB debut until age 26 because he wasn’t good. Rather, his timeline was delayed because of injury. In his first three seasons, McNeil played 117, 123 and 119 games. But in 2016 he played just three games and the following year it was just 48. Without that lost time to injury, McNeil probably makes his MLB debut at age 24, possibly age 23 if everything broke right.

Nimmo – He was slowed by injuries, too, even if not to the extent that McNeil was delayed. Some of Nimmo’s injuries occurred in short-season ball, where he spent two years, before the timeline on our chart began. Also, Nimmo’s rise to full-time MLB player was delayed to injury. His first year with triple-digit MLB games played happened in 2018 and it likely would have happened at least a year earlier if not for injuries at the beginning of that season.

Conforto – His arrival in the majors seems fast but it’s really not that uncommon for a high pick from a major university. The Mets slow-played him in 2015, having him start in Hi-A when he should have been in Double-A. If he had started in Double-A and then got bumped up to Triple-A and then the majors, it would have been viewed as a much-more normal timeline.

Duda – To me, this is close to the upper level of what’s acceptable for minor league assignments for a legitimate MLB starting position player who’s not dealing with injuries.

Alonso – Here we see the Mets’ preference for low initial starting assignments and mid-season promotions play out. Alonso earned the mid-season bump in both 2017 and 2018. And many were annoyed when he didn’t get an MLB promotion in 2018, too. It worked out ok, because the Mets weren’t in a playoff chase in 2018, like they were in 2015 when they called up Conforto. Would they have done the same with Alonso that year if they were?

Davis – He got the call to MLB early in his age-23 season, due to injuries at the MLB level. He most likely would have gotten that promotion by the end of the season. Regardless, we have to wonder if Davis had to work harder to get to the majors, if he would have worked harder more often once he got there.

Tejada – This was the “success” story from when Tony Bernazard was running the minor league system. Bernazard believed in aggressive promotions and initial assignments, sort of a “learn to swim by being thrown in the deep end” way of doing things. The Mets have done a complete 180 since Bernazard left. Perhaps there’s a middle ground out there…

d’Arnaud – Try not to be shocked by this but d’Arnaud had injury issues, too. He only played 71 games in 2010 and in his first year in the Mets’ system, he played just 67. The following season, d’Arnaud played only 50 games, including those in the majors. Counting both majors and minors, d’Arnaud’s season-high in games played is 126. Part of that is because of his position. But injuries have played a big role, too.

Flores – He hit the cover off the ball in the APPY at age 16, which earned him a game at a full-season league. After that, he hit well in Winter Ball, had the Binghamton Bump and also had the good fortune to play his Triple-A ball in the PCL. But his career with the Mets was marked more by a couple of memorable moments, rather than overall good play. Since the Mets cut ties with him, Flores has had a nice career, being utilized mostly as a power righty bat. Josh Satin, with his career .793 OPS versus LHB, wishes clubs would have given him the chance they gave Flores.

Lagares – Like Flores, Lagares benefited from playing in Las Vegas and the PCL. After a 2012 season where he had a very pedestrian .723 OPS at age-23 in Double-A, would Lagares have gotten a shot if the Mets’ Triple-A affiliate had still been in Buffalo, where he likely would have turned in another underwhelming season? Instead, in the Mets’ first season in Vegas, Lagares had a .929 OPS when we weren’t fully aware of how much air that contained.

Eventually, we did a Vegas to Queens MLE that indicated the following adjustments: AVG – 74%, OBP – 81% and SLG – 70%. Lagares’ .346/.378/.551 Las Vegas line had a .256/.306/.386 MLE translation and in the majors, Lagares had a .242/.281/.352 line. What if Lagares was playing in Buffalo and had a .280/.330/.390 line – would he have ever been promoted?

Rosario – We had high hopes for Flores because he was considered one of the top international free agents and then hit right away in this country. We had even higher hopes for Rosario, because he had the same rep and same early performance as Flores. But Rosario continued to perform at the higher levels of the minors. And then he came to the majors and underwhelmed. Well, he’s the Guardians’ problem now, especially with their insistence on batting him and his lifetime .308 OBP in the second slot in the order.

*****

Your take away from this should be the average age of a top prospect at various levels. No doubt some of you will bitch and moan about how few players have come up from the farm system and made an impact. But before you do that, do this same exercise for the Phillies or the Padres or the Pirates and let me know what you find. Because while you may have some expectation about how many hitters with 2,000 PA an organization should have over a dozen or so years, your ideas are likely out of whack with reality.

Nice article. I am struck by how few MLB players we have developed over the time frame you used. McNeil, Nimmo and Alonso are legit big league players who could start on any team. Some of the other players are obviously MLB talent but not complete players although they have stuck at the MLB level. It would be interesting to see how your metrics apply to the Atlanta Braves or the Los Angeles Dodgers or other teams who have developed more homegrown star players.

The last graph went for naught…

There are 30 MLB teams. I have no doubt that the two you mentioned have done better than the Mets in this regard. I also believe other unnamed teams have done better, too. If you asked me where I thought the Mets ranked, I’d guess somewhere between 8-12. Would love it if someone did the research to confirm/reject that.

Fangraphs made data export a membership feature so i did this by hand and half guessed people’s debuts so these are just ballpark numbers.

There were 411 players who amassed 2000 PA from 2010 to now.

Of those 411, i manually narrowed it down to 290 players who debuted after 2010.

So on average each team has produced about 9-10 such position players, which means the Mets have been above average and the 8-12 ranking is probably a good guess.

And just because it was mentioned, the Braves have only produced 8 such players, which means quantity-wise, they are below average.

Thanks for doing this!

And for anyone else reading, the 8 Braves to reach 2,000 PA are: Acuna, Freeman, Gattis, Heyward, Riley, Albies, Swanson and Simmons. I think it’s safe to say that all 8 of these players pretty much reached or exceeded their expected levels while they were minor league prospects. Gattis was a 23rd-round pick who had 2,662 PA in the majors – there can’t be many guys since 2010 who can say that. And the ones who can probably didn’t have a lifetime .476 SLG, either.

Interesting read for sure, thanks. It strikes me anecdotally that the Mets have developed a decent share of big leaguers in the Mets360 era…8-12 sounds good. It begs the question, why haven’t they done better overall? Off the cuff, it seems that their inability to develop depth in the pitching ranks, and especially in the area middle relief, has been the downfall. Not drafting and developing enough guys that could reliably get out big leaguers has hurt repeatedly.

Injuries to pitchers have definitely hurt.

But what’s been the real kick in the pants has been the highly touted guys who just haven’t come thru. Flores was one of the top international guys signed in all of MLB that year. Rosario was ranked as the top overall prospect in MLB by some when he was promoted. Fernando Martinez was considered their top prospect and he flopped.

And while he wasn’t as highly ranked as the other three, Dominic Smith being unable to build on strong years in an injury-shortened 2019 and the truncated 2020 season didn’t help either.

Of course, things would look a lot better from a development standpoint if Gimenez, Jarred Kelenic and Pete Crow-Armstrong hadn’t been traded.